Dancing with Myself,Drifting with My Camera:The Emotional Vagabondsof China's New Documentary

by Bérénice Reynaud

http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/03/28/chinas_new_documentary.html

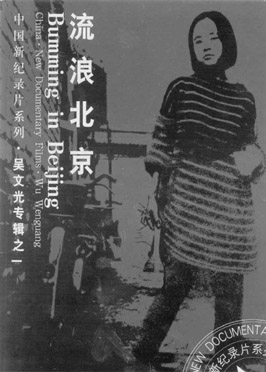

The voices of silence I saw my first Chinese documentary, Wu Wenguang's Bumming in Beijing – The Last Dreamers (Liulang Beijing – Zuihou De Mengxiangzhe, 1990), at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 1991. A young man was taking a hand-held video camera though the streets, back alleys and run-down apartments of Beijing, probing into the daily lives of marginalised artists. Part Jeanne Dielman (for its long takes, mundane actions and empty domestic spaces), part awkward cinéma vérité-cum-talking heads, with a touch of interventionism à la Marcel Ophuls (as Wu sometimes appears in the image and can be heard conversing or arguing with his subjects), Bumming in Beijing, unfolding over 150 minutes, offered access to a China never seen before, and was a genuine breakthrough in formal terms. I have recounted elsewhere, in a text recently quoted in Senses of Cinema, the exhilaration I experienced at discovering this first documentary (1). I was particularly fascinated by the moments in which apparently “nothing happened” and nothing was said. As I was analysing it at the time as a throwback to the tropes of Chinese classical painting (in which “the void” plays an essential part) (2), I was happily challenged by Ernest Larsen's sensitive description of the piece: Wu is not afraid to show us “nothing” – someone cleaning a flat, for example, or making a painting... It is tempting to see this figure of style as distinctively “Chinese” – but the temptation is worth resisting. Furthermore, Wu's long takes and emphasis on duration serve as a kind of counterpoint to the suddenness with which Tiananmen was crushed... The prolonged moments of near silence in Bumming in Beijing produce the aesthetic effect of outlasting the remembered roar of government tanks (3). On the other hand, at crucial moments, Wu adopts a performative mode that goes beyond the tropes of traditional vérité and brings forward his body and his voice, as if to fill the void. Yet, unlike Marcel Ophuls, who inserts his disruptive questions and confrontational humour to track down his interviewee's lies and omissions, Wu stages himself within the picture he (re)creates. The void that structures Bumming in Beijing sends the viewer back to the few months between spring and autumn of 1989 during which no image was taken and death was taking its toll. It is a void that threatened to engulf him as well as his subjects, so the relationship he establishes with them, far from being confrontational, is of shared sympathy. Of the five people whose lives he observes – a female writer (Zhang Ci), a male (Zhang Dali) and a female (Zhang Xia Ping) painter, a photographer (Gao Bo) and an experimental theatre director (Mou Sen) – two define themselves as “vagabonds” (mangliu) (4) either emotionally (Zhang Xia Ping, who later has a nervous breakdown in front of the camera) or professionally (Gao Bo, who equates it to the state of being a freelance photographer (5)). Like them, Wu is an independent artist, unattached to any “work unit”, and working underground – a fate shared by a number of filmmakers of the “Sixth Generation” after 1990 (6).